Introduction

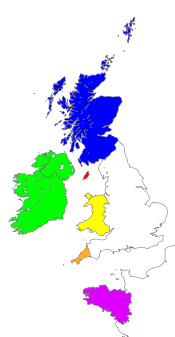

Celtic languages today

Celtic also spelled KELTIC, a branch of the Indo-European language family, spoken throughout much of western Europe in Roman and pre-Roman times and currently known chiefly in the British Isles and in the Brittany peninsula of northwestern France.

The Celtic languages can be divided geographically and chronologically into the Continental Celtic language (or languages) and Insular Celtic.

Pictish is sometimes referred as a 3rd group (- Baldi, Philip.

The foundations of Latin.

New York. 2002.

Continental Celtic languages are generally divided into Lepontic, Celto-Iberian?, and Gaulish and are known to varying degrees from inscriptions and classical references.

The Insular Celtic group consists of the modern Celtic languages, which are generally further subdivided into Goidelic (Irish, Manx, Scottish Gaelic) and Brythonic (Welsh, Cornish, Breton) groups.

History

All Celtic languages are tentatively traced back to Common Celtic, which was the parent language of both the Continental and Insular Celtic languages. Old Irish, the most archaic Celtic language of which substantial records exist and thus the closest in structure to Common Celtic, suggests that Common Celtic retained features of its ancestral language, Indo-European, both in its consonantal and vowel systems and in grammar, or structure. The speakers of Common Celtic probably lived in the eastern part of central Europe, some of them close to the Germanic peoples.

The modern Celtic languages, all of which are descended from Insular Celtic, are the only Celtic languages known thoroughly. In these languages are found a number of linguistic features that seldom occur in other Indo-European languages, features which might possibly be explained by the influence of a non-Celtic people who continued to live in Britain and Ireland after the Celtic settlements of those areas (c. 500 BC).

The Gaelic regions of Ireland, Man, and Scotland shared a common literary norm until the 17th century. The earliest writing is found in ogham inscriptions (ad300-500), a form of writing in which the letters are represented by groups of strokes and notches marked along the edge of stone monuments. Although the origins of manuscript writing in Irish are uncertain, the first extant text, a copy of the Psalms in the Latin script, probably dates from the 6th century. At that time, in any case, there began a great flourishing of literacy and learning in Celtic Ireland, and a substantial record has survived in Irish from the period. Lasting from approximately 600 to 900, it is known as the Old Irish period. The Viking raids of the 8th century disrupted the monastic order, which had guarded the literary norm, and about 900, with the beginning of the Middle Irish period, popular forms began to enter the language. The political turmoil that preceded the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169 may have led to a leveling in the forms of the spoken language. Whatever the case, by about 1200 what is known as the Early Modern Irish period had begun and a new literary norm (called Classical Modern Irish) had established itself. This standard was maintained throughout Ireland, Man, and Gaelic Scotland from the 13th to the 17th century.

In the 17th century, with the centralization of political power in London, the old Gaelic world was fragmented and its shared institutions destroyed. One consequence was the emergence of separate literary forms of Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx, each reflecting local usage. In the case of Manx, continuity with the earlier literary conventions was completely lost.

During the 17th century, a new English-speaking ruling class was settled in Ireland, and the mercantile and professional classes in towns became predominantly English-speaking. By the 18th century, the Irish language was confined to the poorer rural people. After 1745 this effect was also evident in Gaelic Scotland. These populous and impoverished communities were ravaged by economic failure in the 19th century, and survivors began a rapid shift to English. The last speakers of traditional Manx died during the middle of the 20th century. The number of Gaelic speakers in Scotland has declined to about 80,000. In Ireland, the traditional Irish-speaking community has declined to fewer than 60,000 speakers, but the total of those who use Irish habitually in the Republic of Ireland is perhaps more than 100,000, and more than 1,000,000 claim to know it.

Welsh constitutes the oldest attested member of the Celtic language family, with literature (though fragmentary) dating to the 8th century. A continuous record of the language is available from the beginning of the 12th century. By the 15th century the English language had begun to flourish in Wales, but the decline of Welsh was stopped by the Methodist revival of the 18th century, which put Welsh Bibles and other Welsh-language religious books in every home. The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century brought English-speaking workers to the Welsh mines and factories, and the Welsh language again felt the impact of English. By 1901 less than half the population of Wales spoke Welsh and, by the late 20th century, less than a quarter, though much of rural Wales remains Welsh-speaking, and recent efforts have been made to increase its use in the schools.

No literary texts are available for Breton until the 15th century, and from that time the dialects became more and more divergent. In the early decades of the 20th century, efforts were made to standardize four dialects of Breton, but, because of French official policy excluding Breton from the schools, few children learn Breton.

Like those in Breton, Cornish literary texts began to appear only in the 15th century. Although it was still spoken sporadically at the beginning of the 18th century, Cornish had ceased to be spoken by the end of the century.

Language Family Tree

Indo-European > Classical Indo-European > Celtic- Nuclear Celtic

- Cisalpine Celtic

- [xcg] Cisalpine Gaulish

- [xlp] Lepontic

- TGB Celtic

- Insular Celtic (8 languages)

- [xtg] Transalpine Gaulish

- Unclassified Nuclear Celtic

- [nrc] Noric

- [xga] Galatian

- Cisalpine Celtic

- [xce] Celtiberian